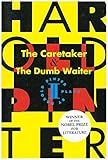

The highlight of my reading life this year was, no contest, the new novel from the Irish volcano Kevin Barry. His Night Boat to Tangier was short-listed for the Booker Prize, and it provides all the pleasures his fans have come to expect, including pyrotechnical language, a delicious stew of high lit and low slang, lovable bunged-up characters, rapturous storytelling, and a fair bit of the old U(ltra) V(iolence), in the form of a knife to a knee, a gouged-out eye, and heart-crushing betrayal. The setup—two aging Irish gangsters waiting for a woman at the ferry terminal in the seedy Spanish port of Algeciras—has obvious echoes of Beckett. But Barry told me in an interview that while writing the book he was actually much more under the sway of Harold Pinter’s early plays from the 1960s, especially The Caretaker and The Birthday Party, with their sneaky undertows of menace. Don’t bother trying to parse the influences. Do yourself a favor and read Night Boat to Tangier, then go to Barry’s earlier, equally brilliant work.

While writing an essay on the great comedian and Blaxploitation star Rudy Ray Moore—occasioned by Eddie Murphy’s comeback role as Moore in the new movie Dolemite Is My Name—I happened upon an insightful book by Jim Dawson called The Compleat Motherfucker: A History of the Mother of All Dirty Words. The book places trash-talkin’, kung-fu-kickin’, full-time-pimpin’ Moore in a context of other broad and bawdy black comedians, from Moms Mabley and Pigmeat Markham through Redd Foxx and Richard Pryor. Dawson makes the valuable point that Moore’s cult status among black audiences was based on his authenticity, which in turn was built on his decision to “stay on the fringes, below white society’s radar.” Smart move. The man was a sui generis genius.

While writing an essay on the great comedian and Blaxploitation star Rudy Ray Moore—occasioned by Eddie Murphy’s comeback role as Moore in the new movie Dolemite Is My Name—I happened upon an insightful book by Jim Dawson called The Compleat Motherfucker: A History of the Mother of All Dirty Words. The book places trash-talkin’, kung-fu-kickin’, full-time-pimpin’ Moore in a context of other broad and bawdy black comedians, from Moms Mabley and Pigmeat Markham through Redd Foxx and Richard Pryor. Dawson makes the valuable point that Moore’s cult status among black audiences was based on his authenticity, which in turn was built on his decision to “stay on the fringes, below white society’s radar.” Smart move. The man was a sui generis genius.

As research for a nonfiction book I’m writing, I read a pair of books that explore the origins and contours of America’s class system. The first was the classic The Mind of the South by a North Carolina newspaperman named W.J. Cash, who committed suicide five months after the book’s publication. Its cold appraisal of the Southern class system, from the loftiest aristocrats down to the lowliest trash, led C. Vann Woodward to call it “the perfect foil” for Margaret Mitchell’s magnolia-scented fantasy Gone with the Wind, published two years earlier. The second book was Nancy Isenberg’s White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America, which generated an unexpected flash of insight: Donald Trump and Andrew Jackson are actually the same person! Isenberg must have been thinking of Trump when she wrote this about Jackson: “Ferocious in his resentments, driven to wreak revenge against his enemies, he often acted without deliberation and justified his behavior as a law unto himself.” She adds that the presidential personality “was a crucial part of his democratic appeal as well as the animosity he provoked. He was not admired for statesmanlike qualities, which he lacked in abundance.” I grew suspicious that Isenberg was writing a cleverly coded takedown of Trump, but I realized that was unlikely because the book was published five months before the 2016 election. And some people still doubt that history repeats itself.

As research for a nonfiction book I’m writing, I read a pair of books that explore the origins and contours of America’s class system. The first was the classic The Mind of the South by a North Carolina newspaperman named W.J. Cash, who committed suicide five months after the book’s publication. Its cold appraisal of the Southern class system, from the loftiest aristocrats down to the lowliest trash, led C. Vann Woodward to call it “the perfect foil” for Margaret Mitchell’s magnolia-scented fantasy Gone with the Wind, published two years earlier. The second book was Nancy Isenberg’s White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America, which generated an unexpected flash of insight: Donald Trump and Andrew Jackson are actually the same person! Isenberg must have been thinking of Trump when she wrote this about Jackson: “Ferocious in his resentments, driven to wreak revenge against his enemies, he often acted without deliberation and justified his behavior as a law unto himself.” She adds that the presidential personality “was a crucial part of his democratic appeal as well as the animosity he provoked. He was not admired for statesmanlike qualities, which he lacked in abundance.” I grew suspicious that Isenberg was writing a cleverly coded takedown of Trump, but I realized that was unlikely because the book was published five months before the 2016 election. And some people still doubt that history repeats itself.

I got my first taste of Edwidge Danticat’s fiction through her terrific new collection of short stories, Everything Inside, deft explorations of the small moments of joy available to the Haitians who populate these tales, set mostly in Haiti and Miami. And finally, on the occasion of Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s 100th birthday, on March 24, I read his new memoir, Little Boy, an ebullient summing up of a century of life richly lived.

More from A Year in Reading 2019

Don’t miss: A Year in Reading 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005