I began 2022 completely out of touch with reality. There were obvious, immediate reasons for this: I was just finishing a kind of improvised book leave where I’d submerged myself for a month in the final edits for my novel. That same month coincided with the height of the pandemic’s winter omicron wave, which meant I’d also been physically cloistering myself at home, with nothing but the echos in my own head and the bass-heavy thudding of my downstair neighbor’s seemingly endless rotation of dinner and karaoke parties. On one hand, I’d never felt more artistically fulfilled. On the other hand, I’d also never felt more alone.

Looking back on the year of reading that followed, I can now see how desperately I grasped for books that could give name to this extraordinary sense of isolation, or at least offer a much-needed tether for feeling my way back to the rest of the world. Sheila Heti’s Pure Colour served as my chief guiding text by offering a deliciously mythologized framework for thinking about creation—that this world is simply the first draft of what a bunch of nameless, ancient gods envision—as well as the personality types that striate humanity according to our predominant affinity for love, art, and justice, respectively. (It’s a novel by a “bird” person, for “bird” people—if you know, you know).

Looking back on the year of reading that followed, I can now see how desperately I grasped for books that could give name to this extraordinary sense of isolation, or at least offer a much-needed tether for feeling my way back to the rest of the world. Sheila Heti’s Pure Colour served as my chief guiding text by offering a deliciously mythologized framework for thinking about creation—that this world is simply the first draft of what a bunch of nameless, ancient gods envision—as well as the personality types that striate humanity according to our predominant affinity for love, art, and justice, respectively. (It’s a novel by a “bird” person, for “bird” people—if you know, you know).

For much-needed real life grounding, I turned to memoirs. Emily Ratajkowski’s My Body proffered excellent essays on self-image and self-ownership. Kelly Williams Brown’s Easy Crafts for the Insane served up almost hilarious proof of how many terrible life events one particularly indomitable spirit withstood nevertheless. Heather Havrilesky’s Foreverland provided a view into her marriage more intimate and unflinching than most relationships I’d observed all my life; there was something about looking at the gears and shifting levers inside the machinery that truly calmed me. Joan Didion’s Slouching Toward Bethlehem, which feels embarrassing to admit to reading at last, was so granular in her decades-old observations that I felt wild with disbelief, to know that humans could really write like that, and see like that.

For much-needed real life grounding, I turned to memoirs. Emily Ratajkowski’s My Body proffered excellent essays on self-image and self-ownership. Kelly Williams Brown’s Easy Crafts for the Insane served up almost hilarious proof of how many terrible life events one particularly indomitable spirit withstood nevertheless. Heather Havrilesky’s Foreverland provided a view into her marriage more intimate and unflinching than most relationships I’d observed all my life; there was something about looking at the gears and shifting levers inside the machinery that truly calmed me. Joan Didion’s Slouching Toward Bethlehem, which feels embarrassing to admit to reading at last, was so granular in her decades-old observations that I felt wild with disbelief, to know that humans could really write like that, and see like that.

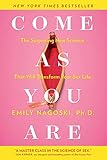

I also read a lot of self-help books, spurred by a summertime trip to Berlin where I found myself earnestly exchanging recommendations with the two other Asian women at the party. We had been having one of those long talks about how much we hungered for specificity, especially when our own lived experiences—not quite just Asian or American, in my case, but a second-generation Chinese American who grew up at the edge of both rural and suburban Illinois—so narrowed the field of art or people or even wording that any of us could truly see ourselves reflected in. I think that’s what drew us to the terminology and pathology we found in books like Bessel van der Kolk’s The Body Keeps The Score, Emily Nagoski’s Come As You Are, The Self-Confidence Workbook by Barbara G. Markway and Celia Ampel, Lindsay C. Gibson’s Adult Children of Emotionally Immature Parents. We whispered their unambiguous titles like guilty confessions, or maybe shared passwords.

I also read a lot of self-help books, spurred by a summertime trip to Berlin where I found myself earnestly exchanging recommendations with the two other Asian women at the party. We had been having one of those long talks about how much we hungered for specificity, especially when our own lived experiences—not quite just Asian or American, in my case, but a second-generation Chinese American who grew up at the edge of both rural and suburban Illinois—so narrowed the field of art or people or even wording that any of us could truly see ourselves reflected in. I think that’s what drew us to the terminology and pathology we found in books like Bessel van der Kolk’s The Body Keeps The Score, Emily Nagoski’s Come As You Are, The Self-Confidence Workbook by Barbara G. Markway and Celia Ampel, Lindsay C. Gibson’s Adult Children of Emotionally Immature Parents. We whispered their unambiguous titles like guilty confessions, or maybe shared passwords.

Of course, this was all very heavy stuff, and I cringe when I think of how incapable I probably was of engaging in normal small talk at the time. What helped then were transportive tales old and new, like Kiley Reid’s Such A Fun Age, Grace Li’s Portrait of a Thief, James Salter’s A Sport and a Pastime (a kind of European vacation in a novella, perfect for August), Bryan Washington’s Memorial, read at long last, which rendered Houston and Tokyo equally vivid (the latter which I explored further with the English translation of Natsuo Kirino’s crime novel, Grotesque). Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities, which felt like accessing a portal to ‘80s New York each night before bed. Torrey Peters’ Detransition, Baby was funny and densely chewy; Ed Yong’s An Immense World was roughly 500 pages of biology made actually delightful. As a committed believer in the art of dream analysis, I also loved Ling Ma’s short stories collection, Bliss Montage.

For days when I couldn’t avoid wondering whether I’d doomed myself to professionally living in my head, two novels about negotiating true happiness in the internet age lent a sense of companionship: Patricia Lockwood’s No One Is Talking About This, about a Twitter personality, and Allie Rowbottom’s Aesthetica, about a 19-year-old Instagram influencer, both made a meal out of the clinical void of online performance that pales in comparison to the sometimes grisly, sometimes tragic reality of medical limitations—reminders that there is anguish, but there also irreplaceable truth, in a living, breathing body.

For days when I couldn’t avoid wondering whether I’d doomed myself to professionally living in my head, two novels about negotiating true happiness in the internet age lent a sense of companionship: Patricia Lockwood’s No One Is Talking About This, about a Twitter personality, and Allie Rowbottom’s Aesthetica, about a 19-year-old Instagram influencer, both made a meal out of the clinical void of online performance that pales in comparison to the sometimes grisly, sometimes tragic reality of medical limitations—reminders that there is anguish, but there also irreplaceable truth, in a living, breathing body.

Unsurprisingly, it was in two definitive works of Asian-American storytelling where I found my surest footing over the year. I read most of Elaine Hsieh Chou’s Disorientation in one frantic gulp while spending the afternoon at a hair salon; never have I felt such an urge to fling a book across a room in public both in reaction to its bonkers (in a great way) plot and also my suspicion that Chou had somehow peered inside a secret inner drawer of my uncategorized thoughts.

Unsurprisingly, it was in two definitive works of Asian-American storytelling where I found my surest footing over the year. I read most of Elaine Hsieh Chou’s Disorientation in one frantic gulp while spending the afternoon at a hair salon; never have I felt such an urge to fling a book across a room in public both in reaction to its bonkers (in a great way) plot and also my suspicion that Chou had somehow peered inside a secret inner drawer of my uncategorized thoughts.

Then, in the fall, I had the privilege of reading Hua Hsu’s Stay True a few weeks ahead of publication, which made the experience of reading it feel private and even more poignant. Compared to the year’s earlier readings, this was not a book short on generational nor personal life traumas either. Still, the purity of one very specific friendship Hsu writes the memoir in honor of was a form of companionship itself. I felt comforted to be reminded once more that connection isn’t some escapist, dramatic affair. Nor is it a thing of sheer fantasy. Rather, true and serious connection creeps up on you, grows as quietly in life as it does on the page, is a construction that results from a thousand individual filaments of time and attention and an unfailing reply to the question, “You, too?”

Then, in the fall, I had the privilege of reading Hua Hsu’s Stay True a few weeks ahead of publication, which made the experience of reading it feel private and even more poignant. Compared to the year’s earlier readings, this was not a book short on generational nor personal life traumas either. Still, the purity of one very specific friendship Hsu writes the memoir in honor of was a form of companionship itself. I felt comforted to be reminded once more that connection isn’t some escapist, dramatic affair. Nor is it a thing of sheer fantasy. Rather, true and serious connection creeps up on you, grows as quietly in life as it does on the page, is a construction that results from a thousand individual filaments of time and attention and an unfailing reply to the question, “You, too?”

More from A Year in Reading 2022

A Year in Reading Archives: 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005