1.

As a life-long lover of long shots, I was delighted by the news that C Pam Zhang’s stunning debut novel, How Much of These Hills Is Gold, made the long list for this year’s Booker Prize. The field was larded with the predictable odds-on favorites, including two-time winner Hilary Mantel (who was up for the third installment in her Thomas Cromwell trilogy, The Mirror & the Light), plus the much-decorated thoroughbreds Anne Tyler (Redhead by the Side of the Road) and Colum McCann (Apeirogon).

Though Zhang’s chances against this field appeared slim, her gorgeously written novel deserves praise not only for its artistry but also for its attempt to fill a shameful gap: the scarcity of Chinese characters in the literature and history of the American West. Yet Zhang’s novel is much more than a long-overdue corrective; it’s an absorbing, richly imagined account of one Chinese family scrabbling to survive the violence and racism that prevailed in the California gold fields and in the gangs that built the transcontinental railroad. Historians have been less neglectful than novelists in probing this material. To name just a few of the many valuable history books: Ghosts of Gold Mountain: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad by Gordon H. Chang; the oral history Voices from the Railroad: Stories by the Descendants of Chinese Railroad Workers, edited by Connie Young Yu and Sue Lee; and Empire’s Tracks: Indigenous Natives, Chinese Workers, and the Transcontinental Railroad by Manu Karuka. Despite these commendable efforts, there are too many stories still untold.

Though Zhang’s chances against this field appeared slim, her gorgeously written novel deserves praise not only for its artistry but also for its attempt to fill a shameful gap: the scarcity of Chinese characters in the literature and history of the American West. Yet Zhang’s novel is much more than a long-overdue corrective; it’s an absorbing, richly imagined account of one Chinese family scrabbling to survive the violence and racism that prevailed in the California gold fields and in the gangs that built the transcontinental railroad. Historians have been less neglectful than novelists in probing this material. To name just a few of the many valuable history books: Ghosts of Gold Mountain: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad by Gordon H. Chang; the oral history Voices from the Railroad: Stories by the Descendants of Chinese Railroad Workers, edited by Connie Young Yu and Sue Lee; and Empire’s Tracks: Indigenous Natives, Chinese Workers, and the Transcontinental Railroad by Manu Karuka. Despite these commendable efforts, there are too many stories still untold.

How Much of These Hills Is Gold opens with two young sisters, Lucy and Sam, setting out to bury their father, a tortuous, gruesome mission that will invite inevitable comparisons to Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying. But Zhang uses this mission as a springboard to tell the story of how the father, Ba, met his wife, Ma, and how they were brought together by a horrific accident and, possibly, by the attack of a mythical tiger. These passages, narrated by Ba from inside his coffin, are the needed beginnings of the creation of an American anti-myth, a first step toward dismantling the widely accepted narrative that the American West was won through rugged individualism, resourcefulness, persistence, and hard work. The truth is that the California railroads were built with taxpayers’ dollars and the sweat and blood of underpaid immigrants who remain largely invisible to this day. That invisibility is at the heart of this novel, and it’s the source of Sam’s desire to cross the Pacific and live one day in a land that might become a true home. “Over there they won’t just look,” Sam says. “They’ll actually see me.”

How Much of These Hills Is Gold opens with two young sisters, Lucy and Sam, setting out to bury their father, a tortuous, gruesome mission that will invite inevitable comparisons to Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying. But Zhang uses this mission as a springboard to tell the story of how the father, Ba, met his wife, Ma, and how they were brought together by a horrific accident and, possibly, by the attack of a mythical tiger. These passages, narrated by Ba from inside his coffin, are the needed beginnings of the creation of an American anti-myth, a first step toward dismantling the widely accepted narrative that the American West was won through rugged individualism, resourcefulness, persistence, and hard work. The truth is that the California railroads were built with taxpayers’ dollars and the sweat and blood of underpaid immigrants who remain largely invisible to this day. That invisibility is at the heart of this novel, and it’s the source of Sam’s desire to cross the Pacific and live one day in a land that might become a true home. “Over there they won’t just look,” Sam says. “They’ll actually see me.”

2.

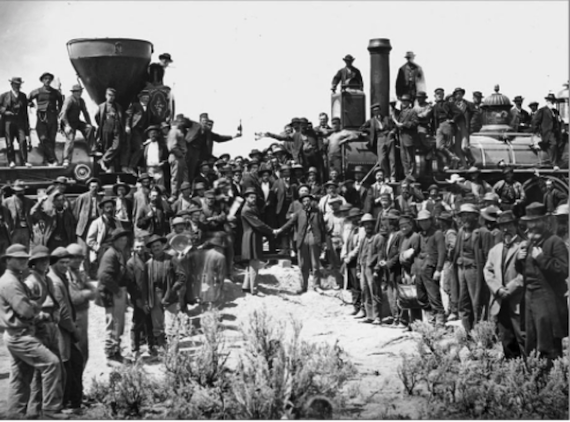

To understand just how overdue Zhang’s novel is, we need to flash back to an event from a century and a half ago that has become a cornerstone of the myth America chooses to believe about itself. On May 10, 1869, a pair of locomotives was parked nose-to-nose on a stark stretch of Utah desert called Promontory Summit. Facing east was the Jupiter of the Central Pacific Railroad; a few yards away, facing west, was No. 119 of the Union Pacific. Standing on the tracks between them with a silver maul in his soft hands was a portly, bearded robber baron named Leland Stanford, a former Sacramento shopkeeper and a former governor of California who had used lavish federal subsidies to buy the land and lay the track from Sacramento to this historic spot. He was surrounded by a boisterous throng of politicians, dignitaries, businessmen, reporters, and photographers. Someone is holding a bottle of champagne aloft, the crowning touch on the nation’s first orchestrated media event. As cameras clicked, Stanford raised the maul and dropped it on a ceremonial golden spike, sinking it into a pre-drilled hole in a laurel tie. The spike was wired to a telegraph line that sent a simple message jittering across the land and, via the undersea telegraphic cable, all the way to the United Kingdom: “DONE!”

The transcontinental railroad was complete. It was now possible for people and goods to travel from the Atlantic to the Pacific on a patchwork of iron rails that had only one gap. The Missouri River would not be spanned for another three years, so passengers and cargo had to be ferried between Omaha, Neb., and Council Bluffs, Iowa. This trifle failed to dampen the spirits of the coast-to-cost celebrants, who were too giddy to be bothered by a few inconvenient truths. The first of these truths is revealed by the iconic photograph of that historic day at Promontory Summit—or, more precisely, by what is missing from that iconic photograph. In keeping with the jingoistic spirit of the pre-packaged event, there are no immigrants in the picture, even though Stanford and his partners—known alternately as the Big Four and the Associates—employed more than 20,000 Chinese laborers to do the brutal, deadly work of blasting a path and laying track from Sacramento through the Sierra Nevada mountains to Utah. And the pay given these laborers? Half of what they paid white workers, mainly Irish immigrants.

That famous photograph finds its way into the closing pages of How Much of These Hills Is Gold. Lucy, now a teenager, has wound up in San Francisco, where she has spent years working off a debt run up by her wild, androgynous sister Sam, who has fled across the Pacific seeking that home where people will actually see her. When the telegraph wire announces that the transcontinental railroad has been completed, Zhang writes of Lucy: “She hears the cheer that goes through the city the day the last railroad tie is hammered. A golden spike holds track to earth. A picture is drawn for the history books, a picture that shows none of the people who look like her, who built it.”

3.

Leland Stanford had been swept west with the gold rush just as the first Opium War and famine were pushing tens of thousands of Chinese immigrants across the Pacific to California, where they flooded the gold fields and joined the gangs of workers laying railroad tracks. (Zhang’s fictional Ma was one of these desperate immigrants; Ba was born in California, a nice dig at the stereotype that all Chinese in the West were recent immigrants.) Inevitably, violence flared between white miners and the Chinese newcomers, and the state responded in 1852 by passing the Foreign Miners Tax—$3 a month on non-citizens—and two years later the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Chinese immigrants, like African Americans and Native Americans, were forbidden from testifying in court, leaving them virtually defenseless against mob violence.

Also missing from the record of that historic day at Promontory Summit are these remarks Stanford had made at his inauguration as governor of California in 1862: “To my mind it is clear, that the settlement among us of an inferior race is to be discouraged by every legitimate means. Asia, with her numberless millions, sends to our shores the dregs of her population…It will afford me great pleasure to concur with the Legislature in any constitutional action, having for its object the repression of the immigration of the Asiatic races.”

It took 20 years for Stanford’s dream to come true in the form of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which suspended Chinese immigration for 10 years and made Chinese immigrants already in the country ineligible for naturalization. It was the first of many laws to restrict immigration, but it fit a pattern already established in California and much of the rest of the nation, a pattern stoked by fear that immigrants would seize jobs from Americans—that is, white people—while depressing overall wages. The 1882 law was also a precursor to the Immigration Act of 1924, which set strict quotas designed to encourage immigration from Western Europe, block most immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe, and bar all immigration from Asia. The law was, in the words of the eugenicist Madison Grant, an attempt to protect Americans from “competition with the intrusive people drained from the lowest races.” It is not a stretch to say that these precedents made possible—even inevitable—the brutal internment of American citizens of Japanese descent after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. This history illustrates that the xenophobia that helped Donald Trump win the presidency in 2016 is nothing new. Such deep-rooted xenophobia in a nation made mostly of immigrants and their descendants is the second of this nation’s two abiding paradoxes. The first, of course, is that men who owned human beings were able to conceive and publicly embrace the notion that all men are created equal.

4.

Now we flash forward to the present day. While the president of the United States strains to build a wall along the Mexican border to repress immigration from Latin America, it comes to light that dozens of people doing menial, low-paying jobs at his resorts and golf clubs are undocumented immigrants from Latin America. So venality and duplicity, like the desire to wall out the “dregs” and “rapists” of an “inferior” race, are simply old pillars of American politics that refuse to die. In keeping with the Sinophobia first codified in the Chinese Exclusion Act, this president has dubbed the current global pandemic “the Chinese virus” and “kung flu.” In doing so, he has completed the second of the two knee-jerk reactions that have greeted the arrival of pandemics throughout human history. The first reaction is denial, which Trump has expressed masterfully; and the second is the need to blame the disease on an outside source. During the plague in Athens in 430 B.C., Thucydides, who contracted the disease and survived, claimed it originated in Ethiopia and passed through Egypt and Libya before entering the Greek world in the Mediterranean. During a smallpox plague in the Roman Empire, Marcus Aurelius blamed Christians, who’d failed to appease the Roman gods. During the Black Death that decimated Europe in the 14th century, Jews were the scapegoat, falsely accused of poisoning wells. Today in America, according to our government, it’s the Chinese—not the appalling failures of our government.

These events, coupled with our current national reckoning over race, make How Much of These Hills Is Gold not only overdue but also vital and timely. As I’d expected, Zhang did not make the short list for this year’s Booker Prize. Unexpectedly, neither did Mantel, Tyler, or McCann. No matter. I’m hoping for many more novels like How Much of These Hills Is Gold: novels that breathe life into people who have gone unseen too long.

Bonus Link:

—A Year in Reading: C Pam Zhang