Wole Soyinka’s literary and activist careers are as marvelous and impressive as his full name, Akinwande Oluwole Babatunde Soyinka, which Pantheon executive editor Erroll McDonald told me to look up. The winner of the 1986 Nobel Prize for Literature, Soyinka is coming out with his first novel in almost 50 years, Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth.

A biting satire that looks at corruption in an imaginary contemporary Nigeria, Chronicles is also an intriguing and droll whodunit. The mystery unfolds around someone trying to stop Duyole Pitan-Payne, a prominent Nigerian and a Yoruba royal, from taking an important post at the United Nations in New York City. Meanwhile, Pitan-Payne’s childhood friend, Dr. Menka, confides that body parts are being stolen from his hospital to be used in rituals. Who is involved and why come together in a brilliant story that takes on politics, class, corruption, and religion from the very first chapters, and that highlights Soyinka’s lush, elegant language:

“That the nation known as the giant of Africa was credited with harbouring the Happiest People in the World was no longer news. What remained confusing was how such recognition came to be earned and, by universal consent, deserved. Aspiring nations needed to be rescued from their state of envious aspiration, a malaise that induced doomed efforts to snatch the crown from their head. The wisdom of elders counsels that it is more dignified to acknowledge a champion where indisputable, thereafter take one’s place behind its leadership, than to carp and wiggle in frustration. When we encounter an elephant, let us admit that we have seen the lord of the forest.”

And this description of a woman: “May I just say that she was like the blending of the kola nuts in the tray she balanced on her head…. I look that skin, and is like God take the red kola and mix it a little with the yellow-white kola nut, and you get a complexion for which even an angel will sell one of his wings, I swear.”

The playwright, poet, essayist, memoirist, novelist, and film writer tells me via Zoom from Nigeria that he did not write this novel “suddenly,” noting, “These ideas have appeared in all my work, my theater, my poems, but I decided they needed an extensive prose treatment.” It took many years; he says he needed “time out of it—time away to write about my country. I had to wait until it was ready.”

Theater, Soyinka tells me, is where he is most at home—“both my work and [plays by] others. I love all of it.” His first major play, The Swamp Dwellers, was written in 1958, when he was 24.

Soyinka calls the Covid-19 pandemic “the nasty icing on the cake” that provided so much time to work. Before the pandemic, he had “carved out spaces,” spending 10 days in a little village in Senegal on the sea and then in Ghana at a residency. The actual writing of the book took close to 12 months, he says, working in a “white heat.” He cites the “trials of computers, losing text, computer crashes,” adding, “I was outside and by myself, and then Covid happened and lockdown.”

Soyinka calls the Covid-19 pandemic “the nasty icing on the cake” that provided so much time to work. Before the pandemic, he had “carved out spaces,” spending 10 days in a little village in Senegal on the sea and then in Ghana at a residency. The actual writing of the book took close to 12 months, he says, working in a “white heat.” He cites the “trials of computers, losing text, computer crashes,” adding, “I was outside and by myself, and then Covid happened and lockdown.”

I ask Soyinka why he’s framed this book as a mystery. “Secretly,” he says, “I always wanted to write a whodunit. This is a confession! I would come across ideas and think, this would make a good mystery. It was always lurking in my mind, so this book was an opportunity to inject a bit of mystery.”

Soyinka sent the first draft of Chronicles to three friends—writers—to ask if it was worth pursuing. “One friend I chose because he’s crazy,” he says. “I told him, ‘I am sending it to you because you are mad.’ ” The other two, he adds, are sane. He also sent it to McDonald.

“I wondered if I had forgotten how to write a novel that was intelligent and intelligible,” Soyinka recalls. “I asked Erroll, ‘Frankly, tell me how you feel,’ and he wrote back enthusiastically.”

McDonald tells me that when Soyinka contacted him to say he had written a novel, he was “thrilled to reconnect and thrilled with the book.” He hadn’t spoken to Soyinka in many years. He says the last time he saw Soyinka was eight or nine years ago at the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard. “I heard someone behind me call out ‘Shadow’—my nickname—and there was Wole.”

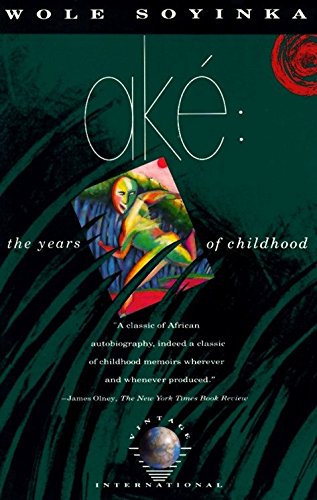

McDonald’s first book with Soyinka was his 1981 memoir, Ake: The Years of Childhood. Five years later, Soyinka won the Nobel Prize, and he invited McDonald to attend the ceremony as a guest.

McDonald’s first book with Soyinka was his 1981 memoir, Ake: The Years of Childhood. Five years later, Soyinka won the Nobel Prize, and he invited McDonald to attend the ceremony as a guest.

“It was my first time,” McDonald says (he went again with Toni Morrison in 1993). “And it was life changing.”

McDonald calls Chronicles Soyinka’s magnum opus. “It’s culturally rooted and scathing in its attitude toward elites, the hoi polloi, everyone,” he says. “Wole is rambunctious; he has such spirit, such linguistic facility.”

The final draft came to McDonald from agent Melanie Jackson, who has represented Soyinka since the early 1990s. She says she heard of the new novel the week before Labor Day 2020 and submitted it in September. “It was a competitive situation that Pantheon won,” she adds.

When I ask how McDonald won it, she’s succinct: “Because Erroll McDonald is great.” The deal for North American and audio was made a few weeks after submission. Pantheon will publish Chronicles in the U.S. in September, and Bloomsbury will release it simultaneously in the U.K. Foreign rights to date have been sold in eight other territories.

Soyinka was a political prisoner in Nigeria in the 1960s and went into exile in 1971. He returned in 1975 and left again in 1994 for exile in the U.S. He was sentenced to death in absentia during the rule of Gen. Sani Abacha. He tells me that exile “has never set well,” calling it a “political sabbatical.” He says he “dealt with the pangs with annoyance and anger—anger that I had to leave in the first place. I didn’t feel pathos, but mostly anger, and when I came back [in 1998, after Abacha’s death], I thought, I hope nothing ever takes me out again.”

About publicity plans, Soyinka is clear: “I’m a minimalist when it comes to hard work. I wish others would take over. My main purpose has been achieved. I’m throwing the baby into the lap of others and wish it good luck!”

This piece was produced in partnership with Publishers Weekly.