The British journalist Sam Leith recently opened a review of Richard Bradford’s Martin Amis: The Biography with the following question: “Where’s Invasion of the Space Invaders? That’s what I want to know.” The 418-page biography, which has been undergoing a sustained critical beatdown since its publication last year, contains no mention of a book Amis published in 1982, and which he has been avoiding talking about ever since. “Anything a writer disowns is of interest,” wrote Leith, “particularly if it’s a frivolous thing and particularly if, like Amis, you take seriousness seriously.” He’s got a point; any book so callously orphaned by its own creator has to be worth looking into. This is especially true if the book in question happens to be a guide to early 1980s arcade games.

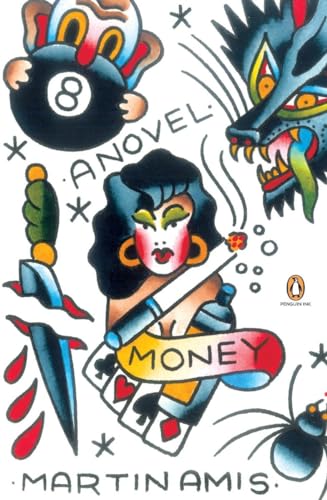

Like most Amis fanciers, I had heard of the existence of this video game book –- the full title of which is Invasion of the Space Invaders: An Addict’s Guide to Battle Tactics, Big Scores and the Best Machines –- but knew very little about it. What I did know was that he dashed it off at some point during the time he was writing Money, one of the great British novels of the 1980s, and that it has long been out of print (a copy in good nick will cost you about $150 from Amazon). And I knew, most of all, that Amis was reluctant to talk about it or even acknowledge it. Nicholas Lezard of The Guardian once suggested to him (facetiously, surely) that it was among the best things he’d ever written, and that it was a mistake to have allowed it to go out of print. “The expression on his face,” wrote Lezard, “with perhaps more pity in it than contempt, remains with me uncomfortably.”

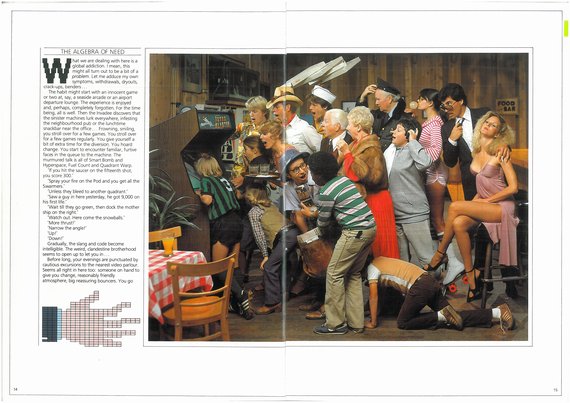

Invasion of the Space Invaders, then, is the madwoman in the attic of Amis’ house of nonfiction; many have heard rumors of its shameful presence, but few have seen it with their own eyes. I recently discovered a copy in the library of the university where I work, and I don’t think the librarian knew quite what to make of my obvious excitement at this coup. (“Wow,” I said, giving a low, respectful whistle as she handed it across the counter. “Would you look at that?”) It’s a deeply strange artifact: an A4-sized, full color glossy affair, abundantly illustrated with captioned photographs, screen shots, and lavish illustrations of exploding space ships and lunar landscapes. It boasts a perfunctory introduction by Steven Spielberg (“read this book and learn from young Martin’s horrific odyssey round the world’s arcades before you too become a video-junkie”), complete with full-page portrait of the Hollywood Boy Wonder leaning awkwardly against an arcade machine like some sort of geeky, high-waisted Fonz. We’re not even into the text proper, and already its cup runneth over with 100-proof WTF.

One of the most frequently remarked-upon aspects of Amis’ writing is that it’s nearly always possible to tell, within a sentence or two, when you’re reading him. (You know it when you see it, with its gimmicks, its lists, its italicized stresses. You know it when you see it, Amis’s style, with its grandstanding repetitions.) And there’s a strange cognitive dissonance that arises from seeing that style applied to what is essentially — or at any rate quickly devolves into — a player’s guide to a range of early arcade games. He starts off with a cluster of short essayistic efforts about game addiction. A few sentences in, and we’re already deep in the familiar, hyper-stylized terrain of Amis country: “What we are dealing with is a global addiction. I mean, this might all turn out to be a bit of a problem. Let me adduce my own symptoms, withdrawals, dryouts, crack-ups, benders…” It’s hard to say who his intended reader might be here. You’d imagine kids would be an obvious demographic target, but that seems unlikely given that Amis gratuitously and jarringly raises the issue of child prostitution on the very first page. (The child sex industry has apparently been given a “fillip” by arcade machine addiction. “Kids,” he assures us, “are coming across for a couple of games of Astro Panic, or whatever. More about this later.”) This slumming fascination with seediness, characteristic of much of Amis’s early and mid-period work, is evident throughout. At one point, we are treated to a series of Hogarthian prose sketches of the grotesques the author sees all around him in these arcades: “Zonked glueys, swearing skinheads with childish faces full of ageless evil, mohican punks sporting scalplocks in violet verticals and a nappy-pin through the nose […] Queasy spivs, living out a teen-dream movie with faggot overtones.” (There’s a glossary at the back that helpfully provides the following clarification: “Faggot: gay.” The word’s use in the original context makes the contemporary reader flinch, but the ugliness of the matter-of-fact definition is downright unforgivable. This is one of several potential reasons why Amis is uncomfortable enough about Invasion to want to keep it out of print.)

The medial bulk of the book is accounted for by the actual “addict’s guide to battle tactics” promised by its ungainly subtitle, and this is where it really flourishes as a bizarro-world extracanonical oddity. It’s as though Kingsley Amis’ youngest son had shied away from the family business and wound up making a living as a games reviewer with a weakness for the high literary style. Here is one of the great aesthetes of the sentence offering tips on dealing with Space Invaders’ descending alien infantry:

The phalanx of enemy invaders moves laterally across a grid not much wider than itself. When it reaches the edge of the grid, the whole army lowers a notch. Rule one: narrow that phalanx. Before you do anything else, take out at least three enemy columns either on the left-hand side or the right (for Waves 1 and 2, the left is recommended). Thereafter the aliens will take much longer to cross their grid and slip down another rung. Keep on working from the sides: you’ll find that the invaders take forever to trudge and shuffle back and forth, and you can pick them off in your own sweet time.

For what it’s worth, this is actually very solid gaming advice. I tested it out on one of those classic arcade websites, and the man knows what he’s talking about — it is all about phalanx-narrowing. (If I ever happen to pass Amis on the opposite side of the street, I’m not sure I’ll be able to prevent myself from shouting across at him like one of the garrulous yobs who populate his novels, “Oi, Mart! Narrow that phalanx!”) He’s technically correct, too, about the fact that, when the aliens descend to the very lowest rung, “you can slide around underneath them, touching them with your nozzle, and survive!” — but I’m not sure he’ll be wanting that sentence to show up in The Quotable Amis, should such a volume ever appear.

He is almost as enthusiastic about PacMan, although you get the sense that he sees it (in contrast to Space Invaders) as a fundamentally unserious endeavor. “Those cute little PacMen with their special nicknames, that dinky signature tune, the dot-munching Lemon that goes whackawhackawhackawhacka: the machine has an air of childish whimsicality.” His advice is to concentrate stolidly on the central business of dot-munching, and not to get distracted by the shallow glamor of the fruits: “Do I take risks in order to gobble up the fruit symbol in the middle of the screen? I do not, and neither should you. Like the fat and harmless saucer in Missile Command (q.v.), the fruit symbol is there simply to tempt you into hubristic sorties. Bag it.” Curiously, for a writer so deeply preoccupied with stylistic refinement and playful innovation — who elevates the pleasure principle to a sort of aesthetic moral law — Amis favors a no-frills approach to gaming. The following piece of Polonian advice pretty much encapsulates his whole arcade ethos: “PacMan player, be not proud, nor too macho, and you will prosper on the dotted screen.” I’m no expert, I’ll admit, but I’ll go out on a critical limb here and suggest that this might be the sole instance of the use of the mock-heroic tone in a video game player’s guide.

Aside from the off-the-charts weirdness of its very existence, the book offers a number of peripheral pleasures. For one thing, there’s a half-expected (but still surprising) guest appearance from what I would be willing to bet is a young Christopher Hitchens. In a diverting rant about the increasing presence of voice effects in games, Amis recalls his first exposure to such gimmickry at a bar in Paris on New Year’s Day, 1980:

I was with a friend, a hard-drinking journalist, who had drunk roughly three times as much Calvados as I had drunk the night before. And I had drunk a lot of Calvados the night before. I called for coffee, croissants, juice; with a frown the barman also obeyed my friend’s croaked request for a glass of Calvados.

Then we heard, from nowhere, a deep, guttural, Dalek-like voice which seemed to say: “Heed! Gorgar! Heed! Gorgar … speaks!

“… Now what the hell was that?” asked my friend.

“I think it was one of the machines,” I said, rising in wonder.

“I’ve had it,” said my friend with finality. “I can’t cope with this,” he explained as he stumbled from the bar.

Elsewhere in the book, he considers the possibility, raised by Paul Trachtman in the Smithsonian, of a future evolutionary strand of video games in which “You have a ten-year reign as a king and you have so much grain, so many people and so much land,” and in which “if you don’t feed your people enough, they start to die.” Trachtman is essentially prophesying the advent of hugely successful games like Civilization and Sim City here, but Amis summarily rejects the idea. “The predictions of the video eggheads are grand and stirring; at the time of writing, though, all the trends in the industry stubbornly point the other way.” Elsewhere, he rubbishes the now-iconic Donkey Kong, the first major success of Shigero Miyamoto, who went on to create Mario and Zelda. “Donkey,” he quips, “your days are numbered. The knackers’ yard awaits you.”

It’s just about possible, if you squint hard enough, to see Invasion of the Space Invaders as Money’s sickly non-fiction twin. Amis occasionally alludes to the fact that all this arcade-lurking and button-bashing is being done both as research for, and at the expense of, a novel he is supposed to be writing. And there are certain advance rumblings here of the comic juggernaut which was to arrive two years later. John Self, for instance — Money’s boorish and omnivoracious narrator — has a particular weakness for a brand of microwaved hotdogs named Blastfurters. In a desultory entry on the game Cosmic Alien, Amis mentions that he first came across it in a “kwik-food beanery on Third Avenue,” where it “looked perfectly at home among the up-ended cartons and the half-eaten blastfurters.” The novel itself features a small but crucial role for its author, whom Self first mentions as follows: “Oh yeah, and a writer lives round my way too. A guy in a pub pointed him out to me, and I’ve seen him hanging out in Family Fun, the space-game parlor, and toting his blue laundry bag to the Whirlomat. I don’t think they can pay writers that much, do you?”

Well, that would certainly be one explanation for this book’s existence; he may have been short of cash at this point, and a brief diversion into video game writing may have been an easy way to turn his coin-devouring addiction to the space-game parlor into a few quid. But there’s an argument to be made that Invasion, as powerfully strange as it looks against the setting of the author’s oeuvre, is in keeping with his perennial preoccupations. Games and game-playing are, after all, both a presiding motif in Amis’s novels and a fundamental principle of their construction. His most successful fictions are arranged around antagonisms, rivalries, and hidden maneuvers. London Fields is an elaborate trap-like construction in which three male characters (including a blocked novelist) are manipulated by a female mastermind into bringing about her own murder. The Information is about a failed writer’s increasingly malicious attempts to destroy the career of his more successful friend. The plot of Money is a Nabokovian conceit in which Self winds up the loser through failing to recognize the game. In that novel’s most bluntly metafictional moment, the character called Martin Amis lets Self in on some of the secrets of his trade: “The further down the scale [a character] is, the more liberties you can take with him. You can do what the hell you like to him, really. This creates an appetite for punishment. The author is not free of sadistic impulses.”

Well, that would certainly be one explanation for this book’s existence; he may have been short of cash at this point, and a brief diversion into video game writing may have been an easy way to turn his coin-devouring addiction to the space-game parlor into a few quid. But there’s an argument to be made that Invasion, as powerfully strange as it looks against the setting of the author’s oeuvre, is in keeping with his perennial preoccupations. Games and game-playing are, after all, both a presiding motif in Amis’s novels and a fundamental principle of their construction. His most successful fictions are arranged around antagonisms, rivalries, and hidden maneuvers. London Fields is an elaborate trap-like construction in which three male characters (including a blocked novelist) are manipulated by a female mastermind into bringing about her own murder. The Information is about a failed writer’s increasingly malicious attempts to destroy the career of his more successful friend. The plot of Money is a Nabokovian conceit in which Self winds up the loser through failing to recognize the game. In that novel’s most bluntly metafictional moment, the character called Martin Amis lets Self in on some of the secrets of his trade: “The further down the scale [a character] is, the more liberties you can take with him. You can do what the hell you like to him, really. This creates an appetite for punishment. The author is not free of sadistic impulses.”

Amis’s characters are always playing and getting played; his books are filled with humiliating drubbings and pyrrhic victories on the tennis court, the pool table, the darts oche. Even that business about which he is most serious — the scrupulous, almost paranoiac abstention from banality at the level of the sentence — is a form of play. The title of his criticism collection, The War Against Cliché, indicates the height of the stakes, but belies the fact that it is ultimately still a game, just one that Amis is very serious about. As a reviewer, he takes a grim satisfaction in catching out his opponents in solecisms, platitudes, and pratfalls (Raymond Chandler’s celebrated hardboiled prose is actually, we are told, “full of stubbed toes and barked shins”). As a novelist, his ludic delight in finding new ways of playing with language — new ways of narrowing the ever-descending phalanx of cliché — is palpable in every sentence. So for all its contextual aberrance, this strange and disreputable book actually makes a certain kind of warped sense. And if for some reason you happen to be looking for a guide to arcade games of the early 1980s, you could probably do a lot worse.

Amis’s characters are always playing and getting played; his books are filled with humiliating drubbings and pyrrhic victories on the tennis court, the pool table, the darts oche. Even that business about which he is most serious — the scrupulous, almost paranoiac abstention from banality at the level of the sentence — is a form of play. The title of his criticism collection, The War Against Cliché, indicates the height of the stakes, but belies the fact that it is ultimately still a game, just one that Amis is very serious about. As a reviewer, he takes a grim satisfaction in catching out his opponents in solecisms, platitudes, and pratfalls (Raymond Chandler’s celebrated hardboiled prose is actually, we are told, “full of stubbed toes and barked shins”). As a novelist, his ludic delight in finding new ways of playing with language — new ways of narrowing the ever-descending phalanx of cliché — is palpable in every sentence. So for all its contextual aberrance, this strange and disreputable book actually makes a certain kind of warped sense. And if for some reason you happen to be looking for a guide to arcade games of the early 1980s, you could probably do a lot worse.