In New York City during late May of 2015, the Rangers professional hockey squad fell just short of the finals, while the Yankees and Mets approached the halfway marker of their seasons clinging to competitive success on the baseball diamond. Andrew Lloyd Weber’s stage adaptation of the Jack Black flick School of Rock appeared primed to draw flocks of the musical-hungry, and word-of-mouth for summer blockbuster Mad Max spread with zest. Mayor Bill de Blasio may have given up on his quest to ban horse rides from Central Park although, then again, maybe he had not. Gun violence, The New York Times acknowledged, had risen without nearing grim levels of an era gone by. Construction proceeded apace on that Department of Corrections-looking astral tower with apartments for the very rich off the southeastern edge of Central Park. Many of us readied for summer escapades. The number of beachgoers at Jacob Riis Park rose again. One World Trade Center recently had opened. New books debuted each and every Tuesday. There were apps for practically everything.

Meanwhile, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, something singular was about to blink out of existence. Although, let it be said, something singular always is about to blink out of existence if you put any stock in venerable city lore: it’s what makes New York New York. Yet Brazenhead Books, some of us want to believe, is the kind of destination New Yorker writer of yore Joseph Mitchell would have commemorated, which is to say, one rooted in the past, a pocket of anomalous culture.

The stroke of genius, Michael Seidenberg, host and proprietor of Brazenhead, will tell you in choosing several years ago to run a speakeasy from his one-time residence, rests in how everyone comes to him. All the book people, anyway. And some aren’t even book people. They just love the vibe.

“I guess for me the social aspect is the main draw — Michael is a gem, the sort of old-school all-around literary guy I haven’t encountered since my early days in NYC in the ’90s, when it already felt like that great old era was ending. It feels like my ideal party. Like many — most, I’d guess — I immediately felt at home,” says novelist Porochista Khakpour. She only recently visited for the first time.

Rachel Rosenfelt, creative director for Verso Books and founder and publisher of The New Inquiry, has visited countless times. She offers a quotation from Lewis Hyde’s The Gift to describe Brazenhead’s draw:

Rachel Rosenfelt, creative director for Verso Books and founder and publisher of The New Inquiry, has visited countless times. She offers a quotation from Lewis Hyde’s The Gift to describe Brazenhead’s draw:

For the slow labor of realizing a potential gift the artist must retreat to those Bohemias, halfway between the slums and the library, where life is not counted by the clock and where the talented may be sure they will be ignored until that time, if it ever comes, when their gifts are viable enough to be set free and survive in the world.

It’s a place that can be mistaken for no other, Seidenberg’s bookstore. Even if that’s really the wrong word. Book-temple kind of gets it while sounding a notch too reverent and as if the environs offered way more space than they do. “That small and sacralized space” is how novelist Scott Cheshire refers to the apartment. “My wife calls it the place where time disappears.” Book-hovel conveys the winding and wending of the corridors through which visitors must pass, along with the no-fuss atmosphere, while failing to get across the distinct sense of wonder. Writer and New York City native Tara Isabella Burton notes “the anarchic spirit” of the place, “which is like every ‘let’s make a pillow fort’ sense of childish wonder meets ‘Beauty and the Beast’ library sense of awe.”

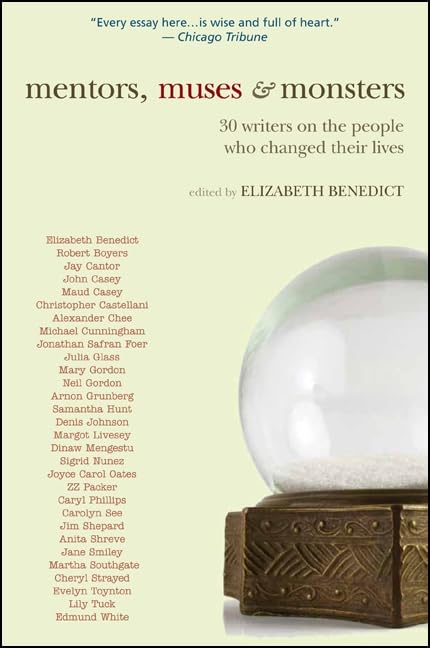

Drinks are perpetually at hand. Between each visit, the books somehow rearrange themselves on the shelves. A title called The Dreams (Naguib Mahfouz) faces outward alongside Arabesques (Anton Shammas). A Newsweek featuring Patty Hearst in black-and-white resides alongside a back-cover emblazoned with Mentors, Muses & Monsters. As when reading a series of diversely authored poems, the mental reflex is to draw evocative links between each one. The titles seem to whisper in cahoots.

Drinks are perpetually at hand. Between each visit, the books somehow rearrange themselves on the shelves. A title called The Dreams (Naguib Mahfouz) faces outward alongside Arabesques (Anton Shammas). A Newsweek featuring Patty Hearst in black-and-white resides alongside a back-cover emblazoned with Mentors, Muses & Monsters. As when reading a series of diversely authored poems, the mental reflex is to draw evocative links between each one. The titles seem to whisper in cahoots.

At Brazenhead, there is no guest list. Maybe an invite or two. The rest of the picture fills in by chance. “It’s a secret club that welcomes all,” says musician Adam Kautz. Every Thursday, every Saturday, apparently since the dawn of time. At least the 19th century? “This place has something of Old Russia about it,” one visitor observed several months ago.

“Unlike most literary parties — which result in a few business cards exchanged, awkward conversations with unimpressive people with impressive bylines, my first night at Brazenhead produced an actual and ongoing relationship to a place and the people in it,” reflects critic Michael Thomsen.

“You really have to fight to maintain any real sense of reliable intellectual fellowship, so to have it provided for you in a super-fucking-cute apartment in Manhattan, whiskey and all, is such a rare gift,” offers fiction writer and recent New York City-arrival Keenan Walsh.

“Brazenhead is a living room in a city where nobody has space for a living room. It’s a community—where the books are both incidental and yet vital,” says Burton.

Who makes up the crowd? Students introduced to the book-haven by their adjunct professors; filmmakers, musicians, actors, and museum workers of most every stripe; psychologists; history buffs; childhood friends of Seidenberg’s; friends of those who have visited before; travelers from Ireland, from Italy, from Spain, from Russia, from Israel, from Lebanon, many of whom read about Brazenhead in a national paper and have arrived from distant lands; magazine editors, book editors, agents, and their assistants who, for the night at least, cease being assistants; book store employees, that endangered breed; and writers, many writers.

The categories of visitor, by the way, are not mutually exclusive.

During an early visit, I found myself in conversation with a smoky-voiced fellow over by the silver-lidded ice bowl. He told me about a 10-hour movie by a French New Wave director, a copy of which he owns. Later that night, young poet, Seidenberg’s right hand, and founder of Brazenhead’s well-attended weekly poetry readings Simona Blat pointed at one of the surrounding bookshelves. The Factory of Facts Luc Sante. The guy had just walked out the door. “That’s him,” she said.

During an early visit, I found myself in conversation with a smoky-voiced fellow over by the silver-lidded ice bowl. He told me about a 10-hour movie by a French New Wave director, a copy of which he owns. Later that night, young poet, Seidenberg’s right hand, and founder of Brazenhead’s well-attended weekly poetry readings Simona Blat pointed at one of the surrounding bookshelves. The Factory of Facts Luc Sante. The guy had just walked out the door. “That’s him,” she said.

Unassuming is the word, incognito the vibe, at Brazenhead. “A book shop,” writes Anatole Broyard in his treasured memoir, Kafka Was the Rage, “should have an almost ecclesiastical atmosphere. There should be an odor, or redolence of snuffed candles, dryness, desuetude — even contrition.” Minus most of the contrition, that description fits the bill. Tobacco smoke spices the air and friendly quantities of marijuana were legalized at Brazenhead at least a few years before the city of New York saw fit to follow suit. The outside world feels somehow suspended under Michael Seidenberg’s roof. Although, it’s true, legality isn’t exactly his raison d’etre, if, in fact, it’s anyone’s. Bob Dylan, The Stones, Tom Waits, and Leonard Cohen are familiars to the stereo system, which is known to have trouble with certain discs. Left to sort itself out, the stereo seems to invent a new form of techno with skipping fragments of “Visions of Johanna,” “Ruby Tuesday,” or whatever else is playing at the moment. Also frequently heard are the tunes of Sixto Rodriguez, a.k.a. Sugarman. These discs, newer to the collection, flow without a catch. Then there’s radio. “I think it’s best when CBS 101.1 is on,” says Kautz.

Seidenberg has held the apartment on 84th Street for 37 years, mostly as his place of residence. In a past life, puppeteering was his primary pursuit. Williamsburg-born, he opened his first bookstore location, which doubled as a base of puppetry operations, in today’s Cobble Hill. This was back when a storefront there went for a song and a dance, both of which Seidenberg could provide with puppets (and the moving company he used to run). Brooklyn now has achieved the quality of myth in his mind; cross the river east and he might dissolve under a sorceress’s spell. Brooklyn was what he aspired so mightily for so long to get out of — why ever go back? That, anyway, is his line. He means it too.

For several years, Brazenhead Books was a basement-level shop on the Upper East Side’s 84th Street. It never exactly did booming business. Regulars included the likes of pioneer Rolling Stone critic Paul Nelson (back in Duluth, Minn., Bobby Zimmerman pirated records from his collection) along with visits from illustrator Jeff Wong, journalist Nik Cohn, film critic Richard Brody, poet Aram Saroyan, and novelist Donald Antrim. Then the ’90s ended. Maintaining the store as rent costs frothed over became fiscally daunting. It was a shame, really, since Seidenberg lived on the same block, a second floor apartment a few buildings away. Tough to beat that commute. He transported his collection to the apartment and he and his wife, Nickita (“Nikki”), relocated within the neighborhood.

For a few years, limbo. On occasion he appeared in a pop-up stall along Central Park’s cobbled eastern border. Maybe you spoke with him there?

Then, inspiration: a close Seidenberg compatriot and art-restorer named George Bisacca along with former Brazenhead assistant Jonathan Lethem (of the Cobble Hill days) helped bring the latest and most unlikely incarnation into existence. It would be a speakeasy from the second-floor apartment, or most of the apartment. A belly-high shelf doubled as a countertop for the store and tripled as a bar immediately beyond the entry vestibule. Seidenberg would locate himself there and, if the day was slow, read the latest fiction to curry his interest.

“He does not have an incurious bone in his body,” says Cheshire.

In addition to recent publications by the younger set, including Cheshire, Khakpour, David Burr Gerrard, and Elliott Holt, well-represented at Brazenhead are house favorites Jerome Charyn, Thomas Berger, Muriel Spark, and Philip Roth. “You don’t need 18 miles of books with a man like Michael curating,” says Tyler Malone, editor-and-chief of lit mag The Scofield. Bob Dylan peers from multiple posters on the walls. A Roger Sterling-looking Joe DiMaggio declares from a 1980s poster-sized ad above the coatrack, “This city wasn’t built by frightened people.” On the shelves running to the ceiling behind Seidenberg’s counter, a strip from a larger painting dangles via a single tack. It features a series of brightly colored abstract shapes, some shadows, and, right at eye level, a bared breast. Just, you know, a conversation piece. Every window is covered, courtesy of interior design firm Whimsy, Flair & Throwback.

Lethem told a few friends about the place and those friends told a few more friends. Patricia Marx showed up for a Talk of the Town piece, noting among other key features the proprietor’s old Brooklyn accent and signature missing teeth (only one readily visible, an upper right incisor). Seidenberg coordinated with visitors via telephone and, “Whoa!” the cutting edge, a social network. For a few years in the late aughts, The New Inquiry made it a headquarters for festivities, hosting frequent readings. “Brazenhead gave me the space in New York City to grow up,” says Rosenfelt. “So few spaces allow that. I found out what I was doing, why I was doing it, what I cared about, and what, if The New Inquiry was going to be a thing, I’d like to have it be.”

From his position at the front of the store, Seidenberg will speak of the New York he knew growing up and what changes the decades have wrought; of his mother and father; of the family dentist to whom he loyally returned for decades as the elder gentleman would remind Seidenberg of his parents; of his wife, Nikki, her years as circulation manager and “emotional lynchpin” for Rolling Stone magazine; of their three-legged pit-bull, Ava, and American terrier, Rosie; of Roy Lavitt, childhood friend, overseas thespian, and head of Brazenhead’s marketing department (i.e. he has drawn cartoons adverting the shop for each incarnation); favorite movies, particularly those starring Burt Reynolds; of the 1980s, a time when so many in the city momentarily lost their way; of culinary achievement (e.g. “Food is something we got right. There are some good snacks…I don’t want to live in a world without snacks. It’s not a Julie Andrews thing, I just like snacks.”); of any writer you care to mention; of various terms ending in ‘-archy’ (e.g. “You can’t fill your beer can with someone else’s whiskey and call it anarchy!”); of how to elicit quick laughter as a puppeteer (trade secret: have the puppets hit each other); of pockets (e.g. “I feel like humans have too many pockets. Half the time I lose things, they’re in my pockets.”); of his adventures as someone licensed to conduct marriages in New York State (i.e. he recently married two writers in a ceremony held on the Brazenhead premises). And that, honestly, is only the tip of the conversational iceberg.

Rosenfelt provides an apt anecdote:

Once, I gave a talk to employees and executives of a Chinese publishing house for Pratt University. They didn’t speak English, so I had a translator with me. I described the importance of informal space and used Brazenhead as an example. After the talk, they approached me to ask if they could visit, which of course I was happy to facilitate. That visit was a true delight for both me and Michael — the space was so special, so essentially New York — they all seemed to light up and told me through their translator that it reminded them why they cared about books. One of them bought Walt Whitman and asked Michael to sign it, as though he was the author. We laughed about it, but I thought that it made cosmic sense. Michael is large, he contains multitudes.

Henry Miller and John Cooper Powys, fixtures of 1920s Greenwich Village, look out in black and white portrait from above a glass-fronted bookcase. Wander from room to room and you will find sections for Art, the Russians, the Japanese, the French, the Spanish, the otherwise translated, the rock ‘n’ rollers, the noir, the erotica, the memoir, The New Yorker writers, the paperback fiction, the poets, the ’60s, the movie-related, the collected letters, the sci-fi, the thrillers, and, all the way in back, replete with cushioned bench for intimate conversation, the first-edition room.

“The best things you stumble across aren’t for sale,” observes editor and critic Brian Gresko, “but are part of Michael’s personal history, or the cultural history of New York City, or, as is often the case, both.”

It was never going to last forever. That, for better and worse, has always been the imminent truth of Brazenhead Books. Scan any of the retro cover designs, titles long out of print, lurid paperback editions, and those that maybe never should have been published to begin with: marooned and made singular by the passage of time, the attrition of their mass-produced peers — curiosities now, corners curled, paper yellowed. Remarkable objects. In effect, the book trove is like a search engine you can stand inside of. Not such an efficient one, sure, but way more pleasurable probably for that very reason.

Word of eviction came down in the fall. Apparently, it is not legal to operate a commercial establishment from a residential apartment.

Following a bout of legal intrigue, final word arrived, an end date, the last hurrah: July 4th, 2015.

As a contributor to The New Inquiry, Seidenberg regularly filed a column called “Unsolicited Advice for Living in the End Times.”

“I’ve accepted the end times,” he says. “Not, like, in a Biblical way. I just did the math.” He may start writing the column again soon under his own banner.

Perhaps it was the tuberculosis speaking, but Franz Kafka also was a writer who had accepted the end times, or at least made a literary ritual of performing with crushing comedic involution the fate in store for the hopeful and bright eyed, his irony as wide across as a blue whale’s jawbone. In the story, “Wedding Preparations in the Country,” Kafka writes from the perspective of a traveler named Eduard Raban, a young man on leave from his office job: “Just recently I read in a prospectus a quotation from some writer or other. ‘A good book is the best friend there is,’ and that’s really true, it is so, a good book is the best friend there is.”

And that sentiment, Kafka’s Kafkaesque-ness notwithstanding, is where Seidenberg and Brazenhead Books figure on the involving literary tapestry of New York City history. (And the place of books in late capitalism — the latter phrase included here in honor of The New Inquiry.) He fostered a place for writers and friends and friends who are writers, and maintained it in its current form, commercial vicissitudes be damned, for almost a decade.

So if you happen to glimpse a few more writers than usual looking disconsolate at the new rooftop bar of your local supermarket or feeding pigeons along the cobbled borders of Central Park, you will know why.

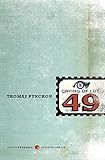

“Excluded middles,” muses will-executor Oedipa Maas in Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 are “bad shit, to be avoided.” Brazenhead Books worked such avoidance pretty deftly. No middle ever was excluded from its quarters. At Brazenhead, the middle has thrived.

“Excluded middles,” muses will-executor Oedipa Maas in Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 are “bad shit, to be avoided.” Brazenhead Books worked such avoidance pretty deftly. No middle ever was excluded from its quarters. At Brazenhead, the middle has thrived.

“We need Brazenhead or something very much like it badly,” says Khakpour. “It’s not optional at this point. Literary culture has become far too corporate — Michael and Brazenhead are reminders of how and why to love books and authors.”

In the months and years ahead, Seidenberg, Nikita, their dogs, plus the lion’s share of his books, will spend more time in a recently acquired farmhouse upstate along the water. Tick-checks promise to become a regular thing. Evenings are likely to consist of watching the river, inventorying the stir of colors along the surface.

Says Seidenberg of sitting there (so contentedly) and watching the river flow, “I used to think it was only a metaphor.”