In the early years of the twentieth century, an eight-year-old girl named Elsie Driggs was traveling by train with her parents from Sharon, Pennsylvania, to New York. She had dozed off by the time the train reached Pittsburgh, but as the writer John Loughery would recount years later in Woman’s Art Journal, her sleep was interrupted: “She was awakened by her father to witness the drama of the black night-sky over Pittsburgh ablaze with soaring flames from the steel plants. It was a memorable sight.”

So memorable that 20 years later, with her artistic career beginning to flourish, Driggs returned to Pittsburgh hoping to recapture the scene in paint. But the fiery Bessemer steel-making process had been abandoned by then, so there were no longer any flames spurting into the night sky. Worse, the local mill’s managers insisted that a steel mill was no place for a young lady—and they were suspicious that she was a union organizer or industrial spy. But Driggs did not give up. “Walking up Squirrel Hill to my boarding house one night, I found my view,” she told Loughery. “It was such a steep hill. You looked right down on the Jones and Laughlin mills. You were right there. The forms were so close. And I stared at it and told myself, ‘This shouldn’t be beautiful. But it is.’ And it was all I had. So I drew it.”

And then she made a painting from her sketches. And then, nearly a century later, while viewing an exhibition of the Whitney Museum’s permanent collection, my eye was drawn to a smallish black-and-white painting—just 34 by 40 inches—that from a distance appeared to be abstract. A miniature Franz Kline? As I got closer I realized it was a stark depiction of cylindrical industrial smokestacks bound by wires at the top left and a gush of smoke at the bottom right. The smokestacks are black and gray, the only color coming from a hint of sulfur in the pale sky. And that’s it: smokestacks, wires, smoke, sky. No flames, no human beings. How did this unremarkable image manage to be so otherworldly beautiful?

The card on the wall told me that the picture was called “Pittsburgh 1927” and it was painted by Elsie Driggs. She soon followed it with an equally stark painting of silos and ducts and smokestacks called “Blast Furnace,” and then a monumental, faceted painting called “The Queensborough Bridge.” These paintings gained Driggs entry into a group dubbed the Precisionists, an informal movement of mostly young artists who in the 1920s were drawn to America’s emerging industrial landscape of factories and skyscrapers and bridges, which they rendered with both a geometric precision that echoed Cubism and a sparseness that sometimes bordered on abstraction, typified by “Pittsburgh 1927.”

A Visual Gold Mine

There were other Precisionists on the walls of the Whitney the day I discovered Elsie Driggs, most notably Charles Sheeler and Charles Demuth. While Driggs was in Pittsburgh, Sheeler was in Detroit on a commission to photograph Henry Ford’s sprawling River Rouge complex, the workplace of 75,000 people, then the largest factory in the world. Sheeler’s assignment was part of the corporation’s publicity campaign for the Model A, which was about to replace Ford’s obsolete Model T. Sheeler spent six weeks roaming the complex with his camera, producing 32 prints that the company used for publicity and that are now regarded as high art. Possibly his most memorable image is “Criss-Crossed Conveyors, River Rouge Plant, Ford Motor Company,” a picture of two conveyors making an X over a tangled netherworld of fences and buildings and ironwork, all of it topped by eight slender smokestacks that reach into the heavens. (A year later, Driggs did a pencil drawing of the same scene.)

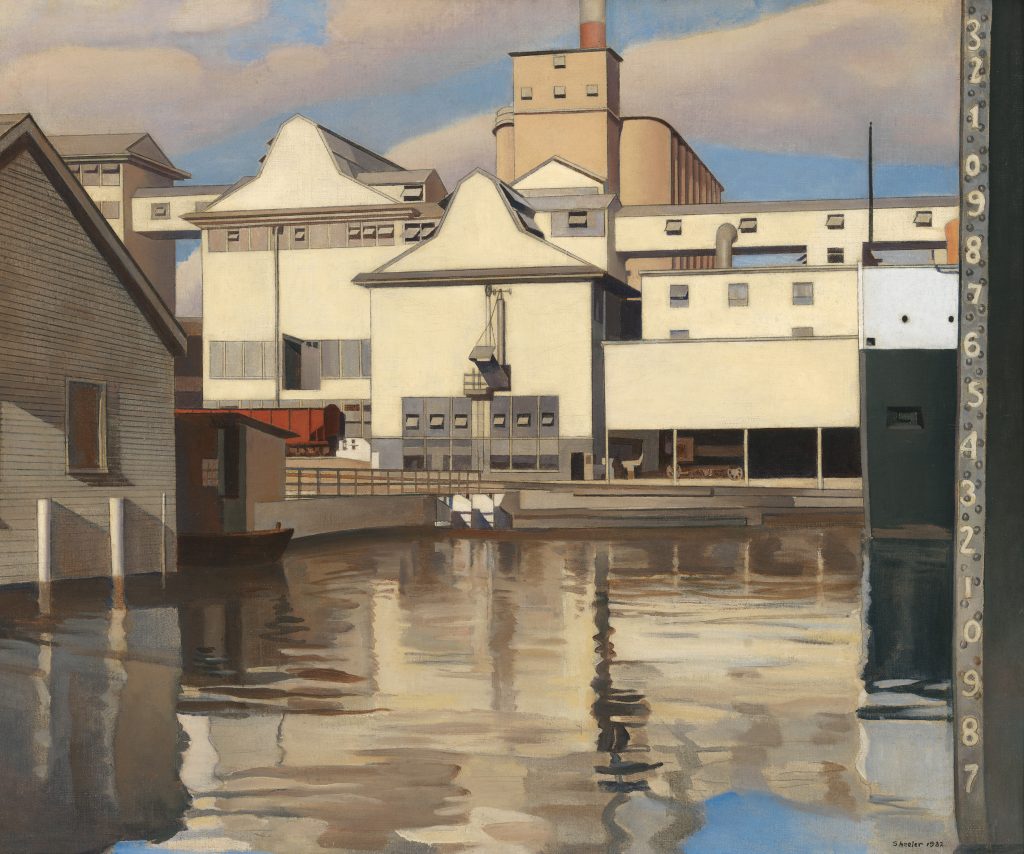

Only one of Sheeler’s works from the Rouge was in the Whitney show—a painting made five years later called simply “River Rouge Plant,” an oddly serene depiction of the factory’s coal processing and storage facility. The exterior walls of the buildings are creamy or tan, the foreground waters of a boat slip are glassy and calm, the sky is blue. There are no workers, no smoke or sparks or grease or slag heaps. The only hint of the repetitive, soul-crushing work that was done there is the nose of a freighter visible on the right. Part of Henry Ford’s genius was to make everything he needed to produce cars—what’s known as vertical integration, the cutting out of all middlemen—and so to make steel he had coal brought up by train from Appalachia, while his fleet of freighters brought iron ore down from Duluth, Minnesota. You would not know this by looking at Sheeler’s stately photographs or serene paintings, nor would you know that Ford was a union-busting anti-Semite who ruthlessly policed the morals of his captive work force. Sheeler was not concerned with such unpleasant facts. For him, all that mattered was that the Rouge was a visual gold mine. “The subject matter,” he wrote to his friend Walter Arensberg, “is undeniably the most thrilling I have ever worked with.” American factories, he added, were “our substitute for the religious experience.”

Hanging on a wall near “River Rouge Plant” was Charles Demuth’s painting “My Egypt” from 1930, a depiction of a grain elevator in his hometown of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The gray structure, topped by exhaust ducts and flanked by a smokestack, is seen from a low angle, giving it a monumental, nearly monstrous presence. Diagonal lines hint at stained glass—and at the notion, widespread at the time among Sheeler and others, that industrial structures were the cathedrals of the machine age.

Only later did I learn that Demuth had painted a picture called “Incense of a New Church” in 1921, which made the link between industry and religion explicit. In the foreground, ropes of smoke—from incense or machines?—coil through a dark world of smokestacks and machinery. Though there are no people visible in either painting, the title “My Egypt” hints at the slave labor that built the pyramids in ancient Egypt and, by extension, at the dehumanizing pressures of the machine age.

But it’s a veiled hint at best. By depicting industrial architecture and machinery but not the humans who built and operated it, the Precisionists left themselves open to the charge that they were glorifying the machine while minimizing or simply ignoring its human costs.

An Ethereal Experience

While Driggs was in Pittsburgh, Sheeler was in Detroit and Demuth was in Pennsylvania, Margaret Bourke-White was in Cleveland photographing the Otis Steel Works. Like Driggs, Bourke-White was drawn to the steel mill by a memory from her girlhood, in this case a visit to a New Jersey foundry with her father. Her recollection of the episode was quoted in the catalog for a 2018 exhibit called “Cult of the Machine” at the de Young Museum in San Francisco: “I remember climbing with him to a sooty balcony and looking down into the mysterious depths below. ‘Wait,’ father said, and then in a rush the blackness was broken by a sudden magic of flowing metal and flying sparks. I can hardly describe my joy…. Later when I became a photographer…this memory was so vivid and so alive that it shaped the whole course of my career.”

Unlike Driggs, Bourke-White gained access to the interior of the Cleveland mill, and after five months she had produced hundreds of prints but only a dozen that satisfied her. One of them, the 1928 print “Otis Steel Works,” was included in “Cult of the Machine.” The picture is an exterior, two railroad tracks running from the bottom left of the frame into the middle distance under an iron bridge. On the left are the brooding vertical forms of the mill, including two stacks that send smudges of smoke into the gray sky; in the middle of it all is a ghostly puff of steam. Only after close looking do you realize that there are two human forms in the distance, under the bridge, reduced to the scale of ants by all this monstrous machinery. In the show’s catalog, the curator Lauren Palmor writes:

Between the steel, iron, and smoke, it is easy to overlook the two minuscule workers in the distance, standing near the tracks like specters. Their diminutive portrayal is consistent with Bourke-White’s early tendency to focus on machines rather than their operators. Even when she includes workers in her images of the mill’s interior, as in this work, they are visually subsumed by machinery, as though they are merely more of its moving parts.

What was behind the Precisionists’ tendency to focus on machines rather than their operators, on the mechanical rather than the human? Was it a way of condemning the pulverizing power of the industrial age? Or was it a way of glorifying these monuments to human ingenuity and will? Or could it be that it was not one or the other, but a bit of both? Or neither?

One possible answer comes from Elsie Driggs. The year she painted “Pittsburgh 1927,” Charles Lindbergh became the first person to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. A year later, Driggs experienced her first flight, aboard a Ford Tri-Motor that carried her from Cleveland to Detroit. It was an ethereal experience, judging by the painting she executed that year, “Aeroplane,” which was included in “Cult of the Machine.” It shows a curvaceous, silvery plane floating through the heavens. Black diagonal lines suggest the whirring of propellers—and identify it as the work of a Precisionist. It’s a lovely, loving homage, clearly a way of glorifying this airborne monument to human ingenuity and will.

“Anything Can Be Interesting and Beautiful.”

The Precisionists are long gone but their impulses live on. A contemporary artist who is also drawn to the pictorial possibilities of American industry is the British-born painter Rackstraw Downes, who has spent the past half century producing plein-air paintings of what he calls “disprized” places—lumber yards, sewage treatment plants, exhausted oil fields, the underbellies of highway bridges and elevated train tracks. He finds most of his scenes near his home in New York and in south Texas, but in 1976 he ventured to Pittsburgh as part of the project by the U.S. Department of the Interior to have 45 artists offer their versions of the American landscape. Downes was given the choice of painting Cape Cod or Pittsburgh. It was an easy call. “Cape Cod is a boring old subject that everybody has done,” Downes told me in a recent interview. “It’s like a warm glass of milk. I like a shot of whiskey myself.”

After driving around Pittsburg for a couple of days, he found his spot: the view from the Clairton-Glassport Bridge over the Monongahela River, with the massive Clairton Coke Works on the right bank. “It was immediately apparent to me that that was the place,” Downes said, echoing Elsie Driggs’s epiphany half a century earlier. “It was the largest coke works in the world. It was sensational with all that smoke going up. It was terribly filthy, and I loved it.” He drew sketches and then completed the painting called “The Coke Works at Clairton, Pa.” that became part of a traveling bicentennial show, “America 1976.” In the foreground, the nose of a barge is visible passing under the bridge while the factory pumps its smoke and toxins into the sky. The barren land on the left bank was, according to Downes, “absolutely dead ground.”

Downes studied literature at Cambridge before he turned to art, and what sets him apart is that he chooses his subjects not only for their visual and sociological properties but also for their potential to produce a narrative. His narratives typically reveal the pulverizing power of the industrial age and, sometimes, the natural world’s way of pushing back. This comes through in his rendering of the Clairton Coke Works in the act of scarring the surrounding river and air and rolling hills. It comes through even more vividly in a 1990 painting called “In the High Island Oil Field, February, After the Passage of a Cold Front.” At first glance, the painting, which is 10 feet long and just 16 inches high, does not seem particularly compelling. It’s a panorama of some wheezing oil rigs and a ditch full of reddish water on a platter of scrub somewhere in south Texas. But if you keep looking, the details begin to multiply—a reminder that Downes paints onsite, without benefit of a camera, sometimes revisiting a spot dozens of times over many months to produce a single picture. And now listen to Downes as he explains what you’re seeing in his 2004 book In Relation to the Whole:

Cows, horses and wading birds share this 1,200-acre field with the pumps, and when strong winds blow in from the north after the passage of a cold front, the sediments that are pumped up with the oil and natural gas and which collect in the bottoms of the ditches are stirred up so the ditch water looks red. The perspective down the center of this painting is the raised embankment of an old railroad bed. The cows like to congregate and lie down to rest on this long-infertile ground because it dries off quickly after a rain; and so they dung it up intensively too. So, it is gradually beginning to regain fertility and support a sparse cover of weeds.… Here the tenses of a landscape imagery which represents what is lost or threatened are reversed; we see decaying industrialization being replaced or reclaimed by the progress of nature. These weeds interest me more than ancient redwoods…

Downes sees beauty and narrative potential even in something as prosaic as razor wire. In 1999, he painted a four-panel series of the coils of razor wire on the fence around a subway maintenance yard in Brooklyn. In a recent phone conversation, Downes tried to explain the visual and sociological elements that drew him to this subject. “If you pay close attention, anything can be interesting and beautiful,” he told me. “I didn’t make the razor wire beautiful. I just painted what was there. Painting it was extremely difficult—the light was always glinting—and it’s vile in its sociological implications. It’s all about keeping people out or keeping people in. It’s nasty stuff.” And yet in his hands it becomes the stuff of high art.

What Downes and these very different artists share is the ability to find beauty in unpromising places. “These industrial forms,” Bourke-White said of the Cleveland steel mill, “were all the more beautiful because they were not designed to be beautiful.” In other words, beauty is not confined to the picturesque vistas that attracted Albert Bierstadt and Ansel Adams and the members of the Hudson River School. Beauty can be accidental, unintended, counterintuitive—even anti-pastoral. And it takes an attuned sensibility to discern such beauty.

All of this is not an attempt to burnish the old chestnut that beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Rather, it’s to suggest that beauty is everywhere if you know how to look for it. Which is what artists like Driggs, Sheeler, Demuth, Bourke-White and Downes know how to do. Beyond knowing where—and how— to look for beauty, they also know how to capture it and present it and make it interesting. This is what elevates them from mere painters and photographers to true artists. I’m reminded of a remark Downes made to me several years ago at the opening of an exhibition of his paintings at the Weatherspoon Art Museum in Greensboro, North Carolina. I asked him about his propensity for choosing subjects that most people think of as anything but beautiful. He replied, “As for beauty, people say to me, ‘Why do you paint such banal subjects? There’s nothing beautiful there.’ It’s not my job to paint something beautiful; it’s my job to make a beautiful painting of something. And that something is something that intrigues me. Sometimes it intrigues me because it’s very modest, very ordinary or very neglected—but I have to have good feelings about it.”

Downes’ remark reminded me of a remark the renowned art critic Henry McBride made in the New York Sun back when “Pittsburgh 1927” was fresh in the world. “Elsie Driggs,” he wrote, “is capable of interesting us in anything in which she herself is interested.”

That, to my mind, is the measure of greatness in any artist.