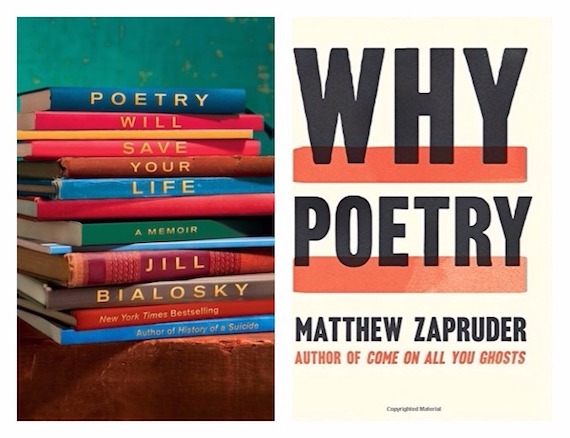

Jill Bialosky author of Poetry Will Save Your Life, and Matthew Zapruder, author of Why Poetry, discuss the state of poetry, their own connection to the art, and their shared experiences as poets and editors.

Matthew Zapruder: What prompted you to write Poetry Will Save Your Life?

Jill Bialosky: I didn’t start out to write a book about poetry. My original conception was a short anthology of poems to live by. I saw a special on PBS introducing poems for children and it struck me that there may be a correlative for adults. Not to dumb down poetry, but to open the door to it for readers who haven’t yet been interested or aware of the possibilities in a poem. As a poet and a poetry editor, I am frustrated by the marginalization of poetry and believe that there’s a larger audience for poetry that it hasn’t reached as of yet, particularly in this country. So I suggested to my editor that perhaps I might curate a short anthology of poems that does just that—speak to a larger constituency and attempt to show how certain poems are made up of and are about everyday living. My focus was not on the theory or making of the art itself, or the writing of the art, but more an appreciation through my own subjective lens. I collected the poems and wrote short headnotes and an introduction and turned it in to my editor. And his response in essence shaped the idea for this book. He said that I hadn’t yet made the book my own. I knew exactly what he meant. Why are these poems important to you? I stepped back and began to think about when I encountered a particular poem and what it meant to me and means to me now, and I found that telling my own stories gave me access to do this. And then the form found its voice. Or the voice found its form. I wrote into my own experience, narrating pivotal moments in my own life to show how certain poems—written through the ages, from poets who have led completely different lives—still can capture a moment, emotion, or experience while using language that is unique to poetry.

How about you, Matthew—what was your original conception for Why Poetry? Did you have a particular audience in mind?

MZ: I wanted to try to directly engage with the typical questions and anxieties so many people have about poetry. I’m sure you have had plenty of experiences with people saying that they don’t get poetry, that they feel like it’s confusing, hard, etc. When I found myself in those situations, instead of turning away, or getting frustrated, I started to talk more with people, to ask them lots of questions, to try to get to the deeper reasons for these feelings about poetry. Eventually, these conversations led me to consider genre: that is, the purpose of poetry as a distinct act in the world. What does it do that is different from prose? Why does it feel so necessary and also so elusive? Is it possible to talk about these things in simple, direct, language, to get to the essence of poetry, without leaving something vital out, or destroying the experience? These were some of the questions I was asking during the writing of the book. I tried to write it for anyone: I feel like my audience is curious people who have any interest at all in literature, or art, or experiences that are beyond the purely functional.

Our books combine personal experience with an impulse to dig into poetry in a way that is careful and close, without becoming purely academic. What did you feel like you learned, about poetry and about yourself as a poet, when you were writing your book?

JB: I love what you say about considering the genre, the purpose of poetry as a distinct act in the world. It’s an art form that in some ways is completely unique. It is the compression and use of language (the craft as it were) and the channeling of actual experience, of lived life, that give it universal power. My presumption is that those who fear poetry or fear an inadequacy in themselves regarding “not getting it” haven’t learned how to read a poem. In Poetry Will Save Your Life, I purposefully chose to write about poems that I found accessible: Robert Hayden’s “Those Winter Sundays,” for example, a portrayal of a young boy’s evolving consciousness as he awakens to hear his father making a fire to heat the house, or Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art” because the form—the villanelle—is playful, and the reader can delight in its use of rhyme but also experience something deeper.

What did I learn while writing the book? That’s a great question. A number of things. Most significant, I recognized how grateful I am that I happened to walk into a poetry workshop as an undergrad, and how that moment eventually led to a direction and purpose I hadn’t yet discovered. I began to see how significant poems can be, and how important it has been through the ages to have poets chart their own experiences. I discovered, in fact, that poetry may indeed have saved my life from a less interesting one had I not discovered it, and it gave me a path forward. The immersive pleasures of poetry have shaped who I am and what I do. And in writing this book I was able to recall those poems that in a sense led me forward or became deeply ingrained in my thinking and imagination.

When was the moment you knew that poetry was essential in your own life and what were some of the poems that awakened you?

MZ: I was telling someone the other day that writing this book was like getting a Ph.D in poetry, except without the benefit of a dissertation advisor. I could have used one. I was reading a lot of poetry, of course, but also trying to read as much as I could about poetry—classic poetic statements from Aristotle to the present. Many of my instincts were confirmed: for instance, that there are, across times and cultures, similar ways of talking about concepts like the poetic symbol, associative movement (the leaping, intuitive aspect of poetic thinking), metaphor, and how poetry renews language. It was thrilling to come upon statements by poets as different as Bashō and Ralph Waldo Emerson and Tracy K. Smith, for example, and to see that they are saying very similar things. I structured some of the chapters around these ideas, and I attempted to show how these concepts recur throughout the history of poetry, in all sorts of eras and cultures. But a lot of my ideas were changed.

For instance, my thinking about symbolism changed pretty radically. When I first started the book, I was pretty sure that symbol hunting—the idea that all poems are codes, that they have secret messages, and that the words in them “stand in” for big, often banal, ideas—was one of the things that we were taught in school that ruins poetry for a lot of people. I still think this is true. But I became very interested in a more historical idea about symbolism, that it has to do with an idea that language is not merely for the purpose of communication, but also points the way toward unseen realms, ideas that we intuit, but are just out of reach of the conscious mind, our everyday experience. I saw this idea stated in many different ways, and saw true symbols in almost all of the poems I love. At some point in the book I say that all poets are, more or less, symbolists, which is the opposite of something I would have said when I first started writing!

My book is, like yours, also structured around the poems that meant a lot to me at various times. The first chapter, “Three Beginnings and the Machine of Poetry,” describes two of my earliest memories of reading poems: Auden’s “Musée des Beaux Arts,” which I came across in high school, and, somewhat embarrassingly, Longfellow’s “The Song of Hiawatha,” which is, to say the least, a racially insensitive poem, but also has a kind of beauty to it that appealed to me. I also have a chapter on a poem by Ashbery, “The One Thing that Can Save America,” which I read when I was first deciding to study poetry instead of being a Ph.D student in Russian literature at Berkeley. I also write about “Those Winter Sundays,” as well as a formal poem by Elizabeth Bishop, “Sestina.”

Did the experience of writing Poetry Will Save Your Life change, reaffirm, or open up certain ideas or possibilities in your own creative work?

JB: Like you, I learned a great deal about poetry writing Poetry Will Save Your Life. It was interesting for me to record the poems I came across and poems taught to me in various classrooms from early childhood—the first poem I remember connecting with was Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken,” for instance. It was read aloud to my fourth grade class. I was an awkward and shy child, and hearing that poem, I made the association that I was different, and that being different might be a strength. In writing my book I was able to chart my own experiences through the poems that were meaningful to me, and in doing so, from a poet’s perspective, I was able to recognize my own influences. For instance, when I took my first poetry workshop in college, we were studying the “deep image” poem and reading poems by Robert Bly and James Wright, so that in essence was my first association with how to make a poem—through an image. In graduate school the narrative poem became fashionable, and we were reading and studying poems by Robert Hass and Larry Levis. I can see that my early poems employed these methods of narrative and image and through employing these methods I discovered more about the possibilities of what a poem could do and be, and what it might unlock in the unconscious.

I’m interested in what you said about whether “symbolism,” looking for clues in poems to solve a puzzle, turned off students from poetry. I recently re-read a Wallace Stevens poem called “Not Ideas about the Thing but the Thing Itself.” This is an astonishing poem on many levels, but what struck me recently is that it describes the art of writing poetry, that a poem creates a new way of seeing or experiencing reality. That, in essence, is “symbolism!” Poems should be read and experienced the same way we experience seeing a play or watching a movie, or looking at a piece of art. Not picked apart. All to say that in writing the book, I was not only seeing the poems that enchanted and provoked me in my coming-of-age with fresh eyes, but also looking at how they were made and what is possible in a poem. The form is elastic and poets through the ages are continually reinventing the form. If anything, writing the book has given me more confidence to explore and take risks.

We are both poetry editors as well as poets. Has writing your book informed the decisions you make about poets you want to take on for the press? And how has writing Why Poetry informed your own creative work?

MZ: I’m not sure it has changed how I edit, at least not yet. My experiences in life and in writing have, over many years, changed me as an editor. I think it’s natural as a young writer to be a little dogmatic, to be searching for what is and is not “good” in poetry, and rejecting certain things, often in extreme terms. In my editing, teaching, reading, and writing, I’m always working on getting outside myself, so I can see and accept more and more poetry. Robert Irwin has that great book of interviews with Lawrence Weschler, Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees, a quote from Paul Valéry, a poet whose writing about poetry is central to my book. As a poet, editor, teacher, and writer about poetry, I want to forget what I think I know about poetry, in order to be able to see it directly and clearly. That’s what I tried to do in writing Why Poetry: to go back to the basics, so that I could investigate and see and explain to myself and others, clearly and honestly, what it is that makes something poetry, and not prose.

MZ: I’m not sure it has changed how I edit, at least not yet. My experiences in life and in writing have, over many years, changed me as an editor. I think it’s natural as a young writer to be a little dogmatic, to be searching for what is and is not “good” in poetry, and rejecting certain things, often in extreme terms. In my editing, teaching, reading, and writing, I’m always working on getting outside myself, so I can see and accept more and more poetry. Robert Irwin has that great book of interviews with Lawrence Weschler, Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees, a quote from Paul Valéry, a poet whose writing about poetry is central to my book. As a poet, editor, teacher, and writer about poetry, I want to forget what I think I know about poetry, in order to be able to see it directly and clearly. That’s what I tried to do in writing Why Poetry: to go back to the basics, so that I could investigate and see and explain to myself and others, clearly and honestly, what it is that makes something poetry, and not prose.

As far as how writing prose affected my poetry, mostly it just made me miss writing poems. It’s been pretty blissful to get back to the particular thinking only poetry allows, and as I have come to realize, my own experience moving from poetry to prose and then back again only reaffirms everything I express in the book about the necessity and distinctiveness of poetic thinking.

Do you feel like the next poems you write will be different or similar to what you have done before? And does that have anything to do with Poetry Will Save Your Life?

JB: Writing this book brought home in a concrete way how the craft of poetry has affected my process of writing fiction, prose, and memoir. And in an off-kilter way it has informed many of the choices I make as an editor. One of the many gifts of a poem is the way it makes clear what I have come to call the overstory of a piece of writing, and the understory. I learned this as a poet, and then later understood it as a reader. A poem’s surface, the way in which it is made through finely tuned attention to craft, argument, and idea gives the reader a pathway to the poem’s understory—what it attempts to say or mean that may not be explicable in any other way. The focus as a young poet on developing my ear, my use of language and of image, of tone and voice, was necessary for all forms of writing. Though I didn’t know it then, when I began to take poetry writing seriously, those early skills allowed me to not only develop as a writer but also as a human being in the world. And these same skills—sensitivity to language, to story, to the way in which a piece of literature expresses that which only that piece of literature has to say—has informed the books I choose to publish and edit. In other words, poetry instructs us to pay attention, to look deeply, and those skills are relevant in all forms of writing and thinking. I would venture to say that poetry writing and reading ought to be required in the same way composition is a requirement in college.

As for whether writing Poetry Will Save Your Life will have anything to do with the direction my new poems will take, I’m not sure. Writing a poem is a mysterious act. I don’t know where a poem will take me until I’ve found a form or image or scene that leads me through it. I always hope to continue to find new ways to reshape and stretch the nature of the medium and see what more a poem can discover and do. Whether I’m successful at it or not is also a mystery.

MZ: Throughout your career as a poet, writer, and editor, you have been committed to creating and supporting literature that makes a difference in people’s lives. You have written about and brought out into the light difficult, intimate subjects that touch so many of us, including the suicide of your sister. You have published so many authors whose work has mattered to so many people. So I think there is no better person to ask: what, if anything, do you think poetry can do for us in these difficult times, when the forces of reaction and anti-intellectualism and spiritual and physical violence seem to be gaining strength?

JB: I have come to believe that being a writer and an editor means that one must also contribute and serve the literary community and to strive to extend beyond that community. As you well know, words are powerful and have the ability to move forward a constituency. As an editor I am privileged to have worked with Adrienne Rich, Ai, Martín Espada, Joy Harjo, Rita Dove, Eavan Boland—and a number of other essential voices in poetry including newer voices such as Major Jackson and Cathy Park Hong—and to witness the ways in which their poems speak to a powerful constituency. Of course, strong poems have the ability to enlighten and to advance change in the reader. It’s a crucial moment for poetry. I fear the forces of reaction and anti-intellectualism, too, and believe that poets have the sensitivity and power to be voices of witness in historic moments. After the election I wrote a poem called “Hot Tub After Skiing: December 2016” that was published in The New Yorker. It is allegoric to a certain extent and it is about this fear you mention, and yet it received a multitude of responses from non-poetry readers who connected with its shared experience. We need poetry now more than ever, if only as an antidote to the corruption, dishonesty, and constant noise surrounding this political moment. If 50-word tweets can excite people, think of what a poem might do!